THE JOY OF GREEK EMBROIDERY

MORE THAN 150 STITCHING STYLES TELL A STORY OF LIFE AND DEATH

By Loukia Richards

Hemline, Crete, 18th century. Embroidery with flowers, animals, and mermaid. The motifs were copied from Venetian lace designs.

Courtesy of Peloponnesian Folklore Foundation Collection Nafplio.

Hemline, Crete, 18th century. Embroidery with flowers, animals, and mermaid. The motifs were copied from Venetian lace designs.

Courtesy of Peloponnesian Folklore Foundation Collection Nafplio.

Embroidery accompanies all aspects of Greek life from birth to death. While the mermaid motif protects newborns against the evil eye, a black cross stitched on the shroud shields the soul against dangers lurking beyond the grave. Embroidery motifs on garments and household or ecclesiastical textiles reveal gender, class, marital status, origins and cultural roots, trade and exchange, conflict and adaptation; they manifest and increase fertility, abundance, happiness.

Fusion of cultures and styles

Although it is often claimed that embroidery comes from Persia, in Euripides's drama Iphigeneia in Tauris" (fifth century BC) embroidery provides the plot twist. In one of theater's most suspenseful scenes, Iphigeneia, the abducted princess of Mycenae and priestess of Artemis in the barbarian Tauris, learns that the stranger she is about to sacrifice is her long-lost brother Orestes. His identity is revealed and confirmed when he describes the intricate embroidery that Iphigeneia mastered when she was young.

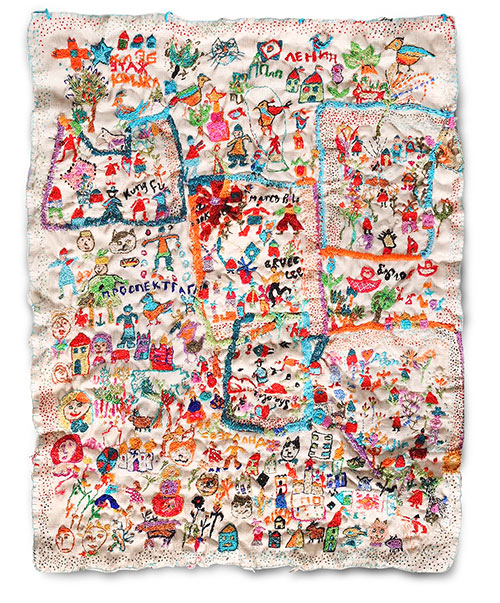

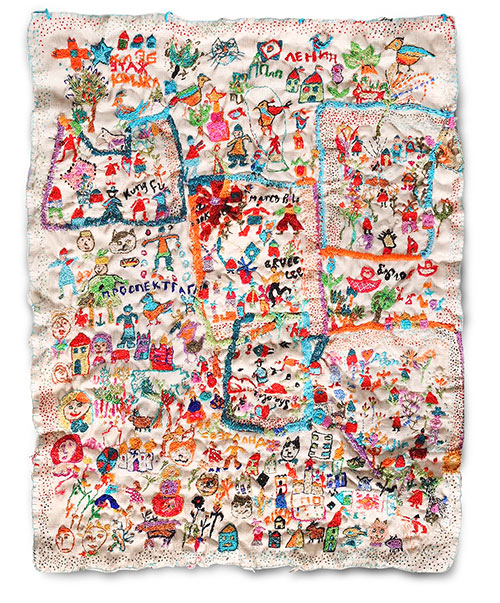

"Prospekt Gagarina", 2008. Embroidery on textile by Loukia Richards. Photo: Studio Kominis Athens.

More than 150 different stitching styles are used to reproduce the rich visual language of Greek motifs that vary from region to region. The same motifs can be traced in sculptural ornaments, mosaics, and murals in Byzantine churches and the sacred manuscripts of Mount Athos. Textile historians note that Greek embroidery is a fusion of traditions that flourished in the eastern Mediterranean. Embroiderers integrated new elements into existing patterns, making 'Greek embroidery' a milestone in textile history. The same motifs can be read as a chronicle of Greece across the centuries. Despite enduring numerous invasions and conquests by foreign armies, Greeks preserved their cultural identity and heritage by adapting to these new conditions, incorporating and Hellenizing them.

"The embroideries were the product of the native culture, fused with the cultures of all the nations that had conquered and settled or had passed through the area," writes Roderick Taylor in his classic volume Embroidery of the Greek islands. "The native Greek culture was based on that of the extended Classical Greek world and on later manifestations of the Hellenistic world, namely Greece, Coptic Egypt, and Byzantium. The conquerors were the Franks and the Latins, Aragonese and Catalans, Venetians and Genoese, and later the Ottomans. Some stayed longer than others and although some influenced the native Greeks and the way they lived, it was the conquerors themselves that were influenced by their stay and it was their lives that were changed."

"Flower Dress", 2022. Embroidery by Loukia Richards. Photo: Chr. Ziegler.

"Flower Dress", 2022. Embroidery by Loukia Richards. Photo: Chr. Ziegler.

The Greeks' intrepid character was shaped by maritime trade dating back to the Copper Age, as epitomized by Homer in The Odyssey. This so-called bible of the Greeks embodies their faith in the concept of life and death – and this has not changed much since the Homeric Age. The brief 'joy of life' is followed by an anemic eternity in the kingdom of shadows.

This 'joy of life' is discernible in all aspects of Greek culture – food, music, hospitality, social gatherings, and celebrations – but finds its most vivid expression in embroidery compositions depicting the united cosmos. In this universe gods, spirits, monsters, angels, humankind, flora, and fauna, both the natural and the supernatural, are presented in detail and exist in their own right.

By comparison, the tunic-shaped shroud, which was the same for everybody, rich or poor, was stitched simply with a cross during the lifetime of the deceased.

READ THE FULL ARTICLE IN THE DIGITAL OR PRINT VERSION...